Many relatively new birders -- those who are essentially trying-out an identity as a birder (i.e., Apprentice Birders) -- start out with quite a zeal for posting their sightings of birds on listserves and other places. And why not? Their interest has not only been piqued, it has been fired up. They are learning to identify birds that many of their friends may not know how to identify and they want to feel like they are an integral part of their new-found birding culture.

|

| Will these observers post their bird sightings? |

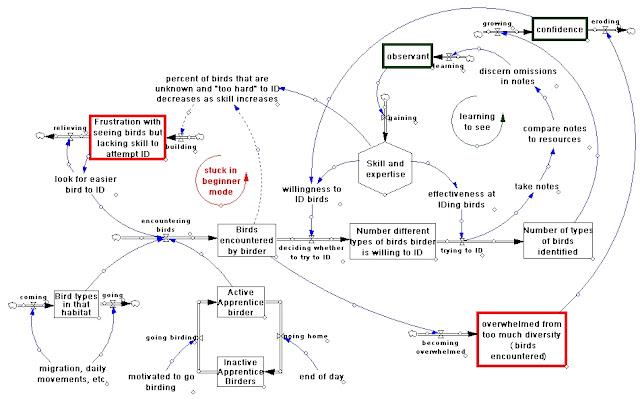

We all get a lot of vicarious enjoyment from folks who post their sightings for all the world to see. I know that I like to know what others are seeing around the local area, and love some of the wonderful anecdotes that folks share along with their sightings. A lot of these new (Apprentice) birders post sightings feverishly for awhile and then stop. Why is that? Do they get tired of reporting the same sightings over and over? Do they stop going birding? If they stop reporting their sightings of common birds, will they still report uncommon birds that other folks might want to go and see? In this blog post, I model a few hypotheses about this kind of behavior by Apprentice Birders. Some of these hypotheses may have ramifications for birder recruitment and retention efforts.

First, I want to discuss the question of why any birders (Apprentices or full-fledged Recruited Birders) report any sightings anyway. In other words, what motivates a birder to report sightings? Social science research suggests that different people may have different motivations for the same behavior, and even one person may have different motivations from time to time (although one motivation is usually is more dominant than others). Some of these different motivations may be: (a) to fulfill a desire to share information with others, (b) to maintain a sense of belonging to birding community, or (c) to let folks know that you're out there looking for, and seeing, birds (i.e., searching for some degree of prestige although nobody would admit to calling it that). As a corollary, people may be motivated to report sightings of rare birds either (a) to fulfill a desire to share information with others, (b) to earn credibility among their birding peers, or (c) to stake a first claim to having found a rare bird (i.e., prevent "poaching" of discovered birds). Hypotheses can fairly easily be developed about any of these different motivations.

Because I want to focus on Apprentice Birders in this blog post, I will limit my models to motivations pertaining to (a) fulfill a desire to share information with others, and (b) maintaining a sense of belonging to the birding community. Both of these motivations (desire to share and desire to feel connected) can be thought of as identity-defining, characteristic traits for some birders. As such, both can be depicted in models as "stocks" (see main page about how to read the components of models) that can increase or decrease depending on certain factors (Figure 1).

|

| Figure 1. Two possible identity-defining, characteristic traits depicted as stocks that can increase or decrease depending on various factors. |

If these are indeed, identity-defining traits of some Apprentice Birders, increasing or maintaining the levels of these stocks would be important motivators for Apprentices to report their sightings of birds -- if those Apprentices linked in their minds (1) reporting birds and (2) increases in one or both of these traits. In a model, it might look something like what you see below (Figure 2).

|

| Figure 2. Reporting bird sightings can help Apprentice Birders feel more connected to the birding community, especially when those sightings are confirmed by others and those other birders thank the Apprentices for reporting the birds. |

In the figure above, I only show "sense of belonging" just to save space. I think that trying to increase one's sense of belonging to a desirable group can be a major motivation for behavior. Similarly, trying to increase or maintain some minimum desirable level of "being a sharer" also likely is a major motivation for reporting behavior. However, reporting bird sightings can be a real 2-edged sword, especially for Apprentice Birders whose excitement level may exceed their level of skill at the finer points of bird identification. Sometimes, Apprentice Birders make mistakes. Every birder does, even the supposed experts. If someone identifies a fall Blackburnian Warbler as an out-of-range Yellow-throated Warbler, it really is no big deal. A few folks may spend gas money and time away from family or work to try to see the more rare species, but the world is not going to end, and they may stumble upons some other interesting birds.

Still, if Apprentice Birders are reporting their sightings in an effort to feel more connected to the birding community, any public notification that they made an identification error -- no matter how tactfully the notification is done -- will depress that sense of being connectied. Further, if the erroneous sighting is corrected in some untactful way, it could lead to an intolerable level of "ridicule." In this case (Figure 3), "ridicule" could be an identity-destroying characteristic. Loss of a "sense of connection" to the birding community is likely to lead to the Apprenitice stopping reporting (because erroneous reporting is draining away that sense of connection). If the Apprentice's feeling of ridicule gets too high, he is likely to actually stop trying to develop his identity as a birder.

|

| Figure 3. Apprentice Birders may be motivated to report their bird sightings to increase their sense of being connected to the birding community, but hearing that they have may an erroneous identification can decrease that sense of connection, and untactful notifcation of their error can lead to intolerable levels of an identity-destroying trait like "ridicule." |

Moral of the model is to take it easy on Apprentice Birders and thank them for sharing their sightings whether or not they made an identification mistake.

Go bird!

.jpg)

.jpg)